S-matrix

In physics, the scattering matrix (or S-matrix) relates the initial state and the final state of a physical system undergoing a scattering process. It is used in quantum mechanics, scattering theory and quantum field theory.

More formally, the S-matrix is defined as the unitary matrix connecting asymptotic particle states in the Hilbert space of physical states (scattering channels). While the S-matrix may be defined for any background (spacetime) that is asymptotically solvable and has no horizons, it has a simple form in the case of the Minkowski space. In this special case, the Hilbert space is a space of irreducible unitary representations of the inhomogeneous Lorentz group; the S-matrix is the evolution operator between time equal to minus infinity, and time equal to plus infinity. It is defined only in the limit of zero energy density (or infinite particle separation distance). It can be shown that if a quantum field theory in Minkowski space has a mass gap, the state in the asymptotic past and in the asymptotic future are both described by Fock spaces.

Contents |

History

The S-matrix was first introduced by John Archibald Wheeler in the 1937 paper "'On the Mathematical Description of Light Nuclei by the Method of Resonating Group Structure'".[1] In this paper Wheeler introduced a scattering matrix - a unitary matrix of coefficients connecting "the asymptotic behaviour of an arbitrary particular solution [of the integral equations] with that of solutions of a standard form".[2]

In the 1940s Werner Heisenberg developed, independently, the idea of the S-matrix. Due to the problematic divergences present in quantum field theory at that time Heisenberg was motivated to isolate the essential features of the theory that would not be affected by future changes as the theory developed. In doing so he was led to introduce a unitary "characteristic" S-matrix.[2]

Motivation

In high-energy particle physics we are interested in computing the probability for different outcomes in scattering experiments. These experiments can be broken down into three stages:

1. Collide together a collection of incoming particles (usually two particles with high energies).

2. Allowing the incoming particles to interact. These interactions may change the types of particles present (e.g. if an electron and a positron annihilate they may produce two photons).

3. Measuring the resulting outgoing particles.

The process by which the incoming particles are transformed (through their interaction) into the outgoing particles is called scattering. For particle physics, a physical theory of these processes must be able to compute the probability for different outgoing particles when we collide different incoming particles with different energies. The S-matrix in quantum field theory is used to do exactly this. It is assumed that the small-energy-density approximation is valid in these cases.

Use of S-matrices

The S-matrix is closely related to the transition probability amplitude in quantum mechanics and to cross sections of various interactions; the elements (individual numerical entries) in the S-matrix are known as scattering amplitudes. Poles of the S-matrix in the complex-energy plane are identified with bound states, virtual states or resonances. Branch cuts of the S-matrix in the complex-energy plane are associated to the opening of a scattering channel.

In the Hamiltonian approach to quantum field theory, the S-matrix may be calculated as a time-ordered exponential of the integrated Hamiltonian in the interaction picture; it may be also expressed using Feynman's path integrals. In both cases, the perturbative calculation of the S-matrix leads to Feynman diagrams.

In scattering theory, the S-matrix is an operator mapping free particle in-states to free particle out-states (scattering channels) in the Heisenberg picture. This is very useful because often we cannot describe exactly the interaction (at least, not the most interesting ones).

Mathematical definition

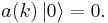

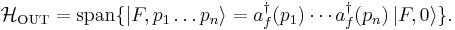

In Dirac notation, we define  as the vacuum quantum state. If

as the vacuum quantum state. If  is a creation operator, its hermitian conjugate (destruction or annihilation operator) acts on the vacuum as follows:

is a creation operator, its hermitian conjugate (destruction or annihilation operator) acts on the vacuum as follows:

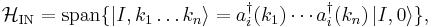

Now, we define two kinds of creation/destruction operators, acting on different Hilbert spaces (IN space i, OUT space f),  and

and  .

.

So now

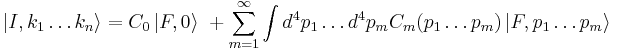

It is possible to play the trick assuming that  and

and  are both invariant under translation and that the states

are both invariant under translation and that the states  and

and  are eigenstates of the momentum operator

are eigenstates of the momentum operator  , by adiabatically turning on and off the interaction.

, by adiabatically turning on and off the interaction.

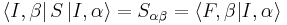

In the Heisenberg picture the states are time-independent, so we can expand initial states on a basis of final states (or vice versa) as follows:

Where  is the probability that the interaction transforms

is the probability that the interaction transforms  into

into

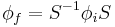

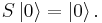

According to Wigner's theorem,  must be a unitary operator such that

must be a unitary operator such that  . Moreover,

. Moreover,  leaves the vacuum state invariant and transforms IN-space fields in OUT-space fields:

leaves the vacuum state invariant and transforms IN-space fields in OUT-space fields:

If  describes an interaction correctly, these properties must be also true:

describes an interaction correctly, these properties must be also true:

If the system is made up with a single particle in momentum eigenstate  , then

, then

The S-matrix element must be nonzero if and only if momentum is conserved.

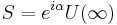

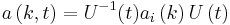

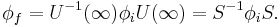

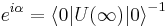

S-matrix and evolution operator U

Therefore  where

where

because

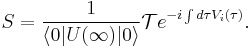

Substituting the explicit expression for U we obtain:

By inspection it can be seen that this formula is not explicitly covariant.

Dyson series

The most widely used expression for the S-matrix is the Dyson series. This expresses the S-matrix operator as the series:

where:

![T[\cdots]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6902ec526cceb5bf3cdfdb262657050a.png) denotes time-ordering,

denotes time-ordering, denotes the interaction Hamiltonian which describes the interactions in the theory.

denotes the interaction Hamiltonian which describes the interactions in the theory.

See also

Notes

- ^ John Archibald Wheeler, 'On the Mathematical Description of Light Nuclei by the Method. of Resonating Group Structure' Phys. Rev. 52, 1107 - 1122 (1937)

- ^ a b Jagdish Mehra, Helmut Rechenberg, The Historical Development of Quantum Theory (Pages 990 and 1031) Springer, 2001 ISBN 0387950869, 9780387950860

References

- Barut, A.O. (1967). The Theory of the Scattering Matrix.

- Tony Philips (11 2001). "Finite-dimensional Feynman Diagrams". What's New In Math. American Mathematical Society. http://www.math.sunysb.edu/~tony/whatsnew/column/feynman-1101/feynman1.html. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

![S = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-i)^n}{n!} \int \cdots \int d^4x_1 d^4x_2 \ldots d^4x_n T [ H_{int}(x_1) H_{int}(x_2) \cdots H_{int}(x_n)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6ee7fb4bccce0f9753dcc0d1fb4597d4.png)